A couple of days ago I came across a story talking about how NASA was interested in helping to interest the next generation of students in science and technology careers (the so-called STEM, or Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics fields). It’s been one of the greater mysteries in technical circles about what caused such a massive fall-off in the number of people pursuing technical degrees in the early 2000s as compared to the 1990s, and most of the obvious explanations (the tech recession in 2000 for instance) have always seemed rather facile to me. I actually think the reason is deeper, and if I’m right then this may in fact be the perfect time for policy makers to be investing in STEM related educational programs.

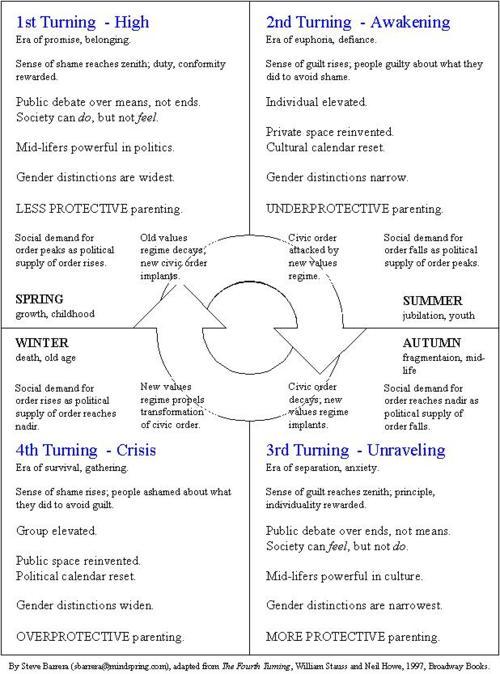

Recently, I had a chance to thoroughly read the classic work The Fourth Turning, by Strauss and Howe. For those not familiar with their theories, the core idea is that there is a societal cycle called a saeculum (from which we derive words like secular) that roughly spans 80-90 years. Each saeculum consists of four generations, each of which tend to have similar values, motivations and philosophies, and each of which interact with the other generations in a clear and distinct pattern. As each generation moves through the various stages of life (youth, adulthood, middle age, senescance) each of which tend to be 18-20 years of length as well, they also tend to have very different concerns, expectations and desires. As prior and succeeding generations are also moving along those same stages but offset, this means that there are distinct configurations that describe the psycho-social characteristics of these generations.

I believe that the current drought in STEM interest (except in certain very specific areas) may actually be generationally driven, and both points to the likely characteristics of the incoming generations and gives a road map that educators and policy makers should pay attention to closely.

A good reference point to show this is to look closely at the Baby Boomers and how they ended up shaping both business and society. The Boomer generation (born from 1943 to 1961, using what I think is a realistic ethical rather than demograph division), for the most part, were not engineers or scientists, though there were several notable engineers and scientists in that generation. It was the GI generation that built the space program, created the first computers, built much of the highway and electrical infrastructure of the country. The Boomers were marketers, managers and salesmen. They were the corporate warriors, and as they moved into the workforce, the engineering ethos of the previous generation was replaced with the marketing ethos of this one.

The GenXers (born from 1962 to 1981), on the other hand, were engineers of sorts, but their playground was not space, but computer technology and biotech. They did the bulk of the programming, designing, engineering and analysis work of the Internet and of the Biotech revolution. What’s interesting is that as the Boomers retire and the GenXers begin to replace them on the other side of the generational gap, the focus of management, of education, and of policy is going to shift increasingly towards problem solving - not “How do we make the most money doing this?” but “How do we solve the problems we’re facing in the most efficient and elegant manner we can?”

I’d argue that this represents a radical shift in thinking in society. It’s hard for a 60 year old C-level manager who’s uppermost thought during the day is “How can we improve the share price of our company?” to understand the motivations of a 42 year old senior engineer who’s looking at finding the optimal solution to building a software system. More significantly, when that 42 year old becomes the 60 year old CEO of the company nearly two decades later, her motivation is not enhancing share price, but building the software products that meet the greatest needs of their customers, with shareholder value far lower on the priority chain. The company structures will be different, the valuation systems will be different, EVERYTHING will be different. They will be focused on SOLVING PROBLEMS.

The Millennials (1982 to 2000), on the other hand, are media people. They grew up in the silver age of Social Media. The Internet had reached a point of complexity that it could start supporting a number of different kinds of media, and the communication aspects of the Internet are far more important to them than the technical aspects. For many of them, there was never a time where the Internet didn’t exist. The oldest of the Millennials are now out of college, they are intensely anti-marketing (this is the generation under which media deconstruction hit its high point) and they are highly genre savvy. This is the generation that will a hundred years from now be seen as the artistic giants of the twenty first century.

However, it is the next generation, what I call the Virtuals (born 2000-2018) that will be the bringers of the next wave of technical innovation (outside the media space). This is a generation that will have high capacity gene sequencers, big data cloud infrastructures and semantically aware computer systems, mobile sensor networks, near-earth commercial space travel, LEDs and memsistors and high voltage solar “fabric” and all the things that are emerging largely from the work of the GenXers (who are now going into research rather than management) before most of them are out of high school.

The oldest Virtual at this point, is twelve years old and is in sixth grade. The youngest will not be born for another six years. The Virtuals are not like the Millennials. I have two children - one born in 1993, the other born in 2000. The elder of the two is a classical Millennial - she’s into cosplay, animation, computer graphics and computer games, and social media. She’s entering college in media arts, and I fully anticipate that she’ll find herself very much caught up in a world where creatives are very much in demand and where the rules of society are rewritten daily. She’s a social deconstructionist.

My youngest was born in 2000, and she is what I believe many Virtuals will be like. She’s more literal than her sister, was programming game levels by the time she was seven (and taught herself how to read off the Internet), and is rather scarily good at finding the information that she needs to educate herself. She’s a technical synthesist. She has trouble with school though, because school doesn’t work the way she thinks - she can find information, but she’s having trouble learning strategies for synthesizing that information. Of course, the schools themselves haven’t really caught up with this fact - they’re just starting to come to grips with the fact that the Millennials exist in a world that is global, is more engrossing than school, and is mediated by networks - and many of those Millennials have already graduated.

As not so much of a diversion here, I think education is a critical part of any society, but I rather despair at the educational system in the US. The content of it is designed by values-conscious Boomers determined to put a stamp of morality and jingoistic patriotism (while minimizing the importance of science in many parts of the country), implemented by technical GenXers who chafe under this system and despairing about the Millennials who all seem like ADHD candidates permanently wired to their smart phones and who for the most part are more interested in video games and cosplay than in IMPORTANT THINGS (even as they themselves wonder whether what they’re teaching is worth anything). And of course, STEM (science, technical, engineering and mathematics) courses of study have seen a massive drop in participation. We’re becoming a nation of gamers and idiots.

Except I’m not so sure that’s really the case. The Millennials are the counter-stroke generation to the Boomers - interested in art and literature, philosophy and media, architecture and music. They are communicators first and foremost, but they really have in the aggregate comparatively little interest in the technical except as it relates to these areas.

The Virtuals, on the other hand, will be technical synthesists. The GenXers have built the scaffolding and infrastructure that the Millennials use for communication and social bonding, but they have also built the scaffolding and very early infrastructure for the Virtuals to build on in combining bio-engineering with information management, for building and designing specialized energy aggregators and generators, and for integrating all of these together into a cohesive technical superstructure of applications (one that reengineers the human body all the way up to the height of the human noosphere). They will in fact be the ones that rebuild the technical underpinnings of society, quite possibly as the world that the Boomers built finally collapses under its own weight.

The GenXers started entering into college (the start of adulthood) in 1982 and its noteworthy that the number of students graduating in STEM technologies started picking up dramatically by 1986. It hit its peak in 1995, four years after the GenXer population peaked (and four years after they entered college). By 1999, even though the tech field was still hot, STEM graduates were declining again. Where were the (now) Millennials going? New media, gaming, communications, web design, graphics, as well as a noticeable pick up in theatre arts, writing, photographer and similar fields. Certainly the technologies were now coming online to make this field attractive, but its worth noting that the place they weren’t going into - not just STEM (except for technology related to the communications revolution) or medicine but also law, finance, business or even the more humdrum aspects of marketing and sales, in places where, ironically, the tools and technologies were just as well developed.

The Millennials are now coming out of college - they hit their peak in 2009 and there’s some evidence to indicate that the number of graduates in the media arts arena is leveling off, consistent with a graduation peak of about 2013. It’s also worth noting that most generations have somewhat different characteristics pre- and post- peaks. Pre-peak generations have shadows of the previous generation that colors their attitudes and beliefs. Post-peak get “premonitions” of the next generation, sharing more and more of their values. At the cusp points between generations, you often end up with people who are generalists, not necessarily strong in any one generation but often being renaissance characters that don’t easily fit into any generation.

If, as I suspect, the Virtuals end up being technological synthesists (as opposed to the GenXer’s role as technological analysts), then 2013 will also mark the trough of STEM graduates, and the trend should turn around. However, their focus is going to shift - alt-energy vs. geologist engineers and chemists, distributed AI construction (possibly with robots and telepresence) vs. business applications, life-form engineers vs. geneticists and oncologists. As a generation they will be very utilitarian and focused compared to the previous generation (whom they will consider as being rather frivolous and perhaps overly indulged). The mid-point in the trend will occur around 2022 with the generation peaking in 2031 in terms of STEM graduates.

Of course, this also brings up an interesting conundrum. The Millennials are for the most part community oriented, though that community is defined virtually rather than physically. This means that their optimal learning style (all other things being equal) is one where learning takes place via interactions with their peers, and social awareness is considered of greater value than technical competence. There, the principle role of the teacher is very much that of the mediator and director, shaping the conversations towards the completion of communal projects.

Virtuals, on the other hand, are already showing that they respond best to autodydactic approaches to learning, where they learn by doing, research what they need when they need it, and generally find traditional teaching methodologies to be confusing at best and counterproductive at worst. As it turns out, this is in fact the best way to learn science, where the role of the teacher is primarily that of advisor rather than authority. The students also tend to gravitate to an apprenticeship model, where you have a master with a limited number of apprentices and sojourners (the pairing of a GenXer with one or more Virtual is a particularly effective combination), especially as the GenXers will be entering Senescence at this stage in their own lives, when their principle role is to be teachers and advisors rather than decision makers.

There’s been a pendulum swing towards anti-intellectualism that seems to be reaching its peak in the US, but we may in fact be near the end of the pendulum swing. The Boomers entered into the period of senescence starting around 2000 (these things tend to be fuzzy +/-3 three years), and the Boomers have generally been the generation of the salesman. In conjunction with senescence this has meant that the Boomers have been focused on physical and financial security, mortality, maximization of financial assets. They also have tended to push conformance to the status quo, which, given the demographic size of the group, has generally meant THEIR status quo, and in old age this has tended to result in dogmatic uniformity, ideological rigidity and a move towards centralization.

By 2009, the peak of the Boomer generation entered senescence (and out of a decision making capacity). By 2018, the Boomers will be completely within senescence, with the GenXers fully invested in the decision-making “Middle Aged” bracket. Since societal direction tends to be determined largely by this bracket, this again hints at society beginning to shift towards more pragmatism, more focus on problem solving rather than profit maximization, and more of a need for (and respect of) scientists and technicians. Just as with the rise of STEM graduates, society itself is beginning to move back towards a mode where the problem solvers, rather than the empire builders, are coming to the fore. Personally, it couldn’t happen soon enough.

One final note. The one area where I break with Strauss and Howe is in their designations of saecular titles. In the fourth turning (the one we’re in now, extending from 2000-2018 +/- a few years) the Millennials are “Heroes” while the virtuals are Artists. I believe that a perhaps more accurate way of thinking is to see Millennials in this phase as Social Deconstructionists (with the Boomers being Social Constructionists, promoting the status quo and GenXers being Technical Constructionists, building technical infrastructure). This means that Virtuals would be Technical Deconstructionists - they will be the mix and match generation, crossing technical disciplines, questioning the technical status quo.

Deconstructionism in literary terms is the process of identifying literary tropes (cultural assumptions), and deconstructing them in an attempt to understand how they work, why they work and how they can then be reconstructed to more closely model the world. Technical construction effectively builds on existing infrastructure to create new works, while technical deconstruction is the process of re-examining those core assumptions, discipline boundaries and underlying physical constraints and create whole new directions with them. The OWS movement is fueled largely by early cycle Millennials (just as the Tea Party is primarily made up of early cycle Boomers). GenXers largely were tool builders, Virtuals will be tool users.

Okay, THIS is the final note and a pet peeve. GenXers have generally gotten a bad rap compared to the Boomers - introverted to the Boomers extroversion, indifferent to material success compared to the Boomers’ avid capitalistic streak, perceptive and slow to make judgements or decisions compared to the Boomer’s decisive leadership and charisma, pragmatists to the Boomers’ idealism. Yet it was the GenXers who were mostly responsible for the creation of the web, probably the single most important invention of the last century. The Internet was initially a construct of the GI generation, while the web was conceived by a late cycle boomer (Tim Berners Lee, born in that incredible technical banner year of 1955, the same year that both Bill Gates and Steve Jobs were born), and implemented for the most part by GenXers (Marc Andreesen, Linus Torvalds, Dan Connolly, Roy Fielding, many others).